The complicated story of why my street in Kyiv changed its name – and why it means so much to me

Street names – when done right – can hold communities' dearest memories. I realized this when one of my family's Kyiv stories began to fade with my grandfather’s advancing Alzheimer’s disease.

Street names are weirdly powerful.

Simple and practical, they infiltrate our minds and stay there for years, often without our consent. As city residents go about their lives, they all carry a shared mind map entangled with the same words and numbers. In a way, street names are our community sticky notes, our collective mind externalized in the material world.

I don’t think people ever intended street names to be that good for memorizing. But it just happens so that putting ideas on a geographical map helps humans remember stuff better. And streets are so much more than just singular objects in space.

Each street is a universe in itself, containing many spots with unique stories: a coffee place where neighbors run into each other; an old bench under a chestnut tree – always occupied by pigeons and elderly folk; a tricky hole in the pavement that always catches your foot.

Moving through these urban stories takes time, focus, and bodily effort – all of which make streets so memorable.

Their perfect memorability makes street names a mighty tool.

Having the power to decide the names of streets means controlling what their residents will remember – and what they will forget. And, as I recently learned, forgetting is inevitable.

That’s why I believe street names should serve the communities that populate them. Let’s have streets capture local stories and memories instead of worshiping hollow concepts.

I think I have a personal story from Kyiv that shows exactly the right and wrong ways to do street names.

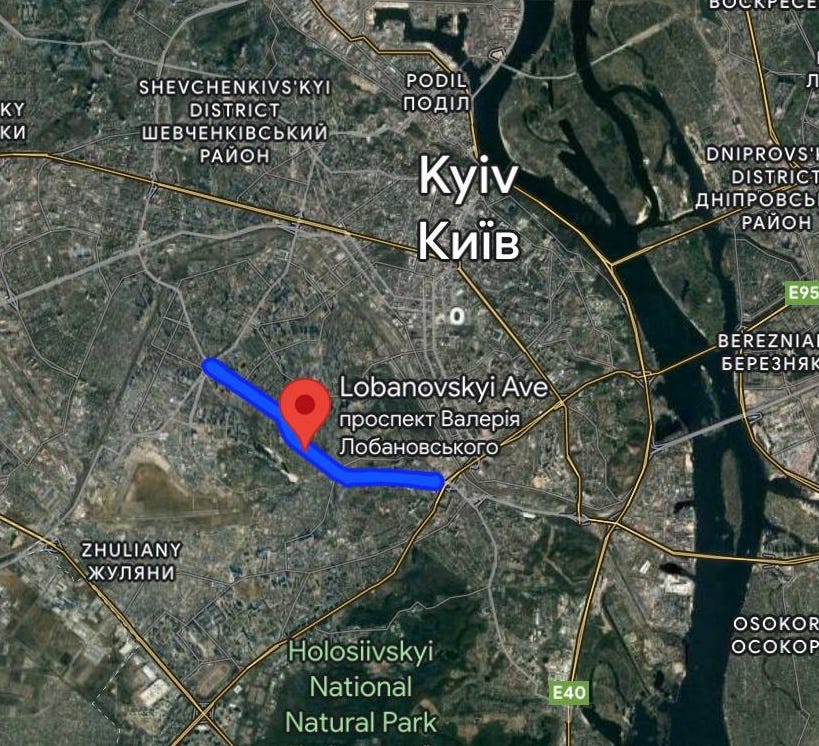

I grew up in the late 1990s and 2000s in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Chervonozorianyi Avenue – “Chervona Zoria” meaning “Red Star” in Ukrainian. A very wide road and almost five kilometers long, it ran down a hill connecting two large districts of a city of 2.5 million people. Just over half a century ago, this area had been a collection of suburban villages hiding between the wilderness of small lakes and bushy hills.

Now, why was the name of my street referring to a red star?

That’s not a very exciting story. Since my street was assembled into one huge avenue in the 1970s, its name was determined by Soviet ideological repetitiveness. The red star was a major Soviet symbol, and there were still countless places across Ukraine named after the red star even a decade after the fall of the USSR.

But as a Ukrainian child born after the fall of the USSR, I hadn’t been indoctrinated with Soviet mythology. I had no idea what “Red Star” really meant.

To me, “red star” could have easily been replaced with “green valley” or “blue sea” without losing any meaning – because there was none.

There were many places, rituals, and words that didn’t make much sense when I was a child. Once bearing meaning in a tight Soviet ideological frame, these semantic ghosts haven’t yet been repurposed in the early years of Ukraine’s breakaway from the empire.

One person who helped me fill these weird gaps between past and present was my grandfather Vova.

Vova was born in 1945 in a house around the same Chervonozorianyi Avenue. He stayed there his whole life, absorbing colossal, generational knowledge of our area.

He knew that the lake next to my house was artificial, and there used to be a little forest in its place. He remembered Chervonozorianyi Avenue before it had been covered with asphalt and given a name. When we walked into the enormous Holosiivskyi forest on the outskirts of Kyiv, he knew every trail and where it led.

Grandpa was also a natural storyteller. Every story he told turned into a comedy performance with dramatic voice effects, hilarious mimics, and, as I suspected later, exaggerations that helped him entertain a restless child’s mind.

One of the coolest stories Vova ever told me happened to be connected to my street and its name.

During one of my hangouts with Vova, we watched a Champions League football match featuring our home team FC Dynamo Kyiv. Things were not going well in that game.

Disappointed, grandpa started reminiscing about how great Dynamo had been just a few years back, in the late 1990s.

He told me that our late-1990s squad had it all: a prodigy and future global superstar Andriy Shevchenko, a deep bench of seasoned veterans and young guns, and a hunger for winning. But above all, they had the late Valeriy Lobanovsky, a legendary coach who had just come back to the club in 1996.

Grandpa Vova then casually dropped:

“Lobanovsky was a genius. He had been like this since he was a kid when I saw him practicing after school.”

Wait, what?

Turns out, Vova and Valeriy went to the same school right next to the house where I now lived.

Six years younger than the legendary coach, Vova used to watch young Valeriy outmaster the entire school and train after classes. As Vova got older, he started going to the stands of the Dynamo stadium, where Lobanovsky – now part of the Dynamo’s squad – produced wonders on the pitch.

Lobanovsky’s worldwide fame came later in life when he switched to coaching. From the 1970s to his death of a heart attack in 2002, he laid the blueprint for modern coaching with FC Dynamo Kyiv and the USSR national team, earning the reputation of the “father of data-driven football.”

And in all of this outstanding career, FC Dynamo Kyiv circa 1998 was Lobanovskyi’s last great achievement. That team went on to reach the quarterfinals and semifinals of the Champions League in the 1997/1998 and 1998/1999 seasons, beating Europe’s heavyweights along the way, most notably 4:1 and 3:0 against FC Barcelona, 2:0 against FC Real Madrid.

The fact that my grandad had known Lobanovsky from the 1950s and had gone to the same school with the legendary coach – a school on my native Chervonozorianyi Avenue – was probably the coolest fact about my neighborhood.

I cherished this story way into adulthood.

I was 20 years old in 2015 when Chervonozorianyi Avenue was renamed and given the name of Valeriy Lobanovskyi.

The renaming was part of a wider decommunization process that had started after the Revolution of Dignity, a democratic revolution against a corrupt dictator, succeeded in February 2014. Decommunization was meant to free Ukraine from the troubling Soviet legacy and finally let the Ukrainian people define their symbols.

The renaming of my street was only the tip of the iceberg of all the societal changes triggered by the revolution. But it’s hard to overestimate the significance of this renaming for my family.

Because right around that time, my grandfather Vova started forgetting things.

“Forgetting things” is how my grandmother Vira described a subtle change in him, a change nobody else noticed at the time. He was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, but it was already too late to prevent further decay of his mind.

In a span of just a few years, I witnessed my grandad turn from the soul of any gathering, a man of gazillion jokes and explosive laughter, into a silent shadow of himself.

Grandpa is 78 now, but he’s not really with us anymore. He hasn’t said a coherent sentence in years, and our family can only guess if he recognizes our faces. His life is completely dependent on the daily caregiving from my grandmother.

Like with so many of his anecdotes, I never got the chance to hear that Lobanovsky story again as an adult.

I almost forgot it at some point. Like many precious things in life, this memory got cluttered lost in the growing clutter of adult life.

But just a few months ago, Lobanovsly’s name came up at a dinner I had with my friends.

One of us recalled how he had been obsessed with Lobanovskyi’s genius back in the 90s. As he was describing the meticulous mastermind of Lobanovsky, the childhood memory fired back at me:

My grandad went to school with Lobanovskyi! I know where that school is, I grew up next door! How cool is that?

It was a bizarre feeling. I was starstruck in retrospect. The weight and significance of this memory hit me for the first time in my adult life. Thinking about it on my way home, now far from Kyiv, I also remembered that the entire five-kilometer-long street of my childhood now carried the name of Valeriy Lobanovsky.

My little family story is now written into our street.

A deep sense of calmness and gratitude filled me.

Even if I’m the only person carrying this tiny memory thread, the street’s name will help me preserve it. And even if my memory fails me someday, the connection between Valeryi Lobanovsky and my native neighborhood will be encoded in Kyiv for generations to come.

Maps will be printed with Lobanovsky’s surname firmly seated on this street. The stream of life running through the buildings – people moving in and out of them, people growing up and dying in them – will leave a trace of paperwork and personal stories.

All these future artifacts from our neighborhood will be pointing back to Valeriy Lobanovsky.

The link has been established. It will stay there, outside of the fragile mechanics of human memory.

I believe there is something deeply righteous about giving the names of streets back to the communities that inhabit them.

There is also something precious about streets holding memories when human brains fail to maintain them – a community looking out for its members in the most unexpected way.

There is no way to prepare for when Alzheimer’s disease strikes your immediate family. One moment your favorite person is with you, another moment they are gone, still sitting right near you. You can’t know what they’ll forget next until they do forget something precious, and you’re left with bottomless regret.

But even a healthy human brain isn’t a reliable way to store memories. We forget stuff easily, and our recollections mutate and disintegrate with time without us realizing it.

That is why I believe we should use street names to preserve stories too important to forget.

Instead of worshiping abstract concepts like red stars, let’s capture things that actually mean something to the people walking the streets.

So that when we do eventually forget, our streets will be there to remind us.

This essay should have ended right there. Unfortunately, it can’t.

I would love for this story to be just that: a story of the hidden meaning of street names and my grandfather’s fading memory. But it’s not.

This is also a story of defending people’s memory against a violent force that wants to erase it.

My street had its name changed to something meaningful because Ukraine enjoyed three decades of independence from the totalitarian, imperialist rule of Moscow.

As a society, we had time to understand ourselves better and revisit the stories we had been told about ourselves. Kyiv grew enough muscle to get rid of faceless Soviet symbols and empower local heroes like Valeriy Lobanovsky.

But this space for collective self-reflection is not a given.

For the last 10 years, and especially since February 2022, Russia has been trying to conquer Ukraine, exterminate our culture, and wipe out our identity.

In the first days of the full-scale invasion of 2022, a Russian missile hit a residential building on Lobanovskyi Avenue. The missile tore out a hole the size of a villa in the 25-story building. That hole was repaired after the Russian army left the Kyiv region later that year.

But things much worse than are happening in other places across Ukraine.

The areas of Ukraine occupied by Russia face forced erasure of local memory. Apart from torturing and killing the locals, Russians also destroy Ukrainian books and rename our streets, districts, and entire towns to worship Russian and Soviet imperial symbols.

This war is just as much about collective memory as it is about geopolitics.

To preserve our memories from violent extermination, Ukrainians have no choice other than to win the war.

If Ukraine is left without continuous support – or if this help is sabotaged and delayed by the infighting of our partner countries – Russians will eventually conquer Kyiv.

Beyond much greater evils that the Russians will unleash on my city, there will also not be a street honoring Valeriy Lobanovsky anymore.

My grandfather’s story will survive only in my mind.

Until time inevitably washes it away.

🔥🔥🔥

Beautiful post. Very touching. Слава Україні 🇺🇦